Document Type : Original Research Article

Authors

- Fadhil Hussam 1

- Shaymaa Abdulhameed Khudair 2

- Waleed K. Alkhafaje 3

- Yasir S. Alnassar 4

- Rashad M. Kaoud 5

- Ahmed Najm Abed 6

- Haneen Saad Jabbar 7

- Hiba Ali Numan 8

1 College of Medical Technology,Medical Lab techniques, Al-farahidi University/ Iraq [email protected]

2 Al-Nisour University College, Iraq

3 Anesthesia Techniques Department, Al-Mustaqbal University College, Babylon, Iraq

4 The University of Mashreq, Baghdad, Iraq

5 Department of pharmacy, Ashur University College, Baghdad, Iraq

6 Al-Esraa University College, Baghdad, Iraq

7 Department of Nursing, Al-Zahrawi University College, Karbala, Iraq

8 Al-Kafeel University, College of Health and Medical Technologies, Department of Medical Laboratory Technologies, Iraq

Abstract

Background & Objective: Infertility is the inability to become pregnant despite trying for at least a year. Infertility is also referred to as when a woman continues to experience miscarriages. Environmental factors, lifestyle, hormone issues, physical problems, and age can all contribute to female infertility. About 10-12% of couples struggle with infertility, a multifaceted issue with ramifications for society, the economy, and culture. The majority of female infertility cases are caused by issues with egg production. By analyzing samples from infertility clinics, the current study aims to investigate the degree of female infertility in Erbil, Iraq, while covering all facets of the condition.

Materials & Methods: 595 infertile females receiving medical counseling from three infertile institutions between February 2020 to December 2021 were screened for the current study. In addition to anthropometric measurements, information about the etiology, duration, and lifestyle, factors of infertility has been gathered using a standardized questionnaire. Additionally, the sample was subjected to clinical examinations. Five groups of reproductive abnormalities were identified. Around 61.79% of women in the infertile group for the first two years had tubal obstruction, and 49.92% had hormonal deficiencies. Ovulation defects (4.62%) and undersized uteri (4.82%) predominated in the >10-year infertile group. Both weight and body mass index have shown a favorable association with infertility duration.

Results: Our findings demonstrated a significant correlation between body mass index and infertility. Most academic and wealthy groups pursued medical advice to resolve issues related to infertility.

Conclusion: Finally, it is suggested that female infertility can be managed and cured with hormone therapy, laparoscopic procedures, minor surgical procedures, and medicine.

Highlights

✅ Finally, it is suggested that female infertility can be managed and cured with hormone therapy, laparoscopic procedures, minor surgical procedures, and medicine.

Keywords

Main Subjects

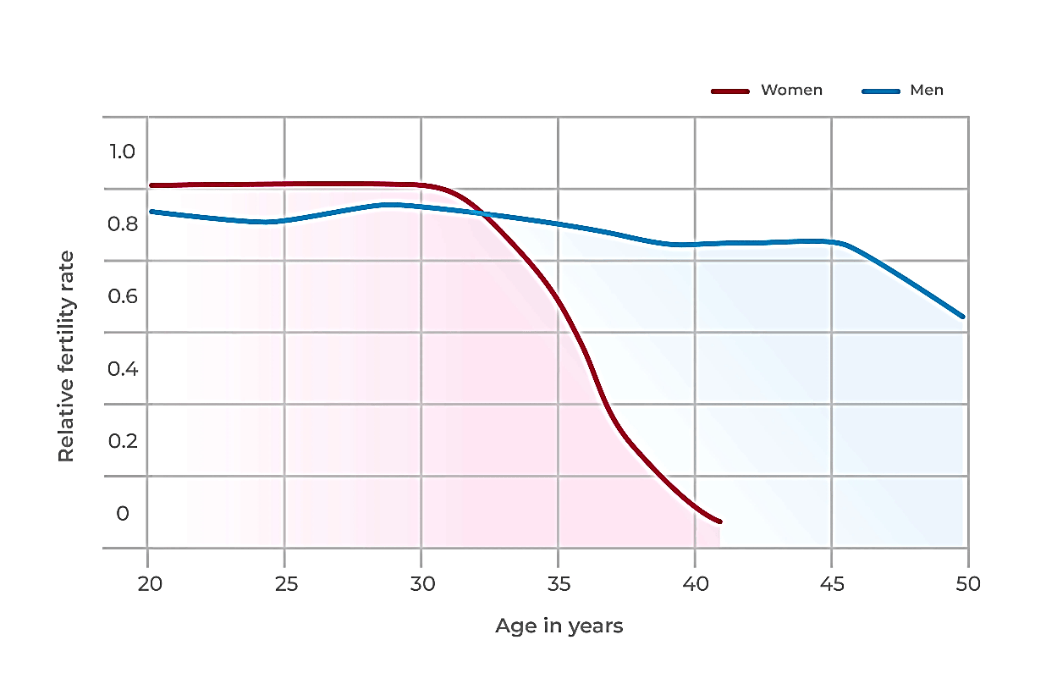

Failure of a couple to conceive within a year of unprotected sexual activity is referred to as infertility (1,2). Infertility is a condition that affects people in every community around the globe. However, the root causes and severity of the issue might differ depending on factors such as socio-economic status and geographical location (3–5). An estimated 10 to 15% of couples struggle with infertility, and female factor infertility accounts for more than half of all instances (6,7). Failure to ovulate, which affects 40% of women who struggle with infertility, is the most frequent general cause of female infertility (8,9). As a result, it is a widespread disorder that has significant financial health repercussions as well as psychological ones that cause desperation (10). It's important to remember that infertility isn't only a health issue; it's also a matter of societal inequity and unfairness (11). Infertile women reported mental issues such as decreased sexual satisfaction, worry, loss of focus, melancholy, anxiety, and loneliness (12). The couple's inability to have children is their primary concern, even though the medical issue is infertility. Couples that experience infertility typically attribute about one-third of instances to the woman, one-third to the man, one-third to how the two interact, and 20% are unaccounted-for (13,14). On the other hand, it would appear that the woman is almost always held accountable for the infertility of a relationship. As a result, she is frequently subjected to social and psychological repercussions (15). In any culture where having children is integral to a woman's sense of self-identity and motherhood carries a high social weight, infertility can leave women with unhealed emotional and social wounds (16). Infertility can be caused by a variety of medical disorders (17,18). In reality, different medical issues cause the majority of cases of infertility. These issues may result in hormonal issues, harm the fallopian tubes, or impede ovulation (19). Polycystic ovaries syndrome (PCOS) is one of the main medical problems linked to infertility. Up to 90% of ovulation cases are caused by it, which is typically an inherited issue. In addition to having multiple small cysts on their ovaries and high levels of androgens, women with PCOS may not ovulate (20). Weight gain, infertility, acne, excessive hair growth, and missed or irregular periods are all symptoms of PCOS. Obesity and insulin resistance are both directly tied with PCOS (21,22). Hyperprolactinemia, hypothyroidism, and hyperthyroidism are three hormonal abnormalities that affect ovulation (23). 6 to 10% of all females suffer from the debilitating condition of endometriosis. 35 to 50% of women with pain, infertility or both will experience this (24). Age causes a decrease in fertility. A woman in her late teens to late 20s is at the height of her reproductive potential. However, after the age of 27, it starts falling, and after the age of 35, it falls at a slightly faster rate. By 45, fertility has decreased to the point where most women find it difficult to conceive naturally (Figure 1) (25).

Figure 1. The effect of age on fertility

Losing weight or gaining too much with a body mass index (BMI) of more than 27 kg/m2 can result in ovarian dysfunction (26). The effectiveness of treatment and the results of assisted reproductive technology have been proven to be impacted by excess weight (27). A healthy lifestyle is vital to prevent infertility, even if no known nutritional or dietary treatments are available. By altering behavior patterns, some ovulatory issues may be resolved. It's crucial to maintain a healthy weight since people who are either overweight or underweight run the risk of experiencing fertility problems, which includes having a reduced success rate with fertility treatments (28). It is essential to keep a healthy weight since individuals who are either overweight or underweight are at risk for infertility. Individuals with unhealthy weight have a decreased probability of being successful with fertility treatments. Given this context, the current study aims to examine the extent of female infertility in Erbil, Iraq, by taking samples from infertility clinics. These clinics offer sufficient infrastructure facilities for every type of clinical investigation of infertility, whether male or female.

From February 2020 to December 2021, we conducted a cross-sectional study in Erbil, Iraq. The in-vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment center in the Maternity Hospital served as the recruitment site for all participants. All the women who took part in the study were at least 18 years old, had been given a diagnosis of infertility, and were fluent in Arabic. A sample size of 595 infertile women was chosen by convenience sampling for this cross-sectional descriptive study, which also evaluates their health and reproductive status. The study materials were from IVF treatment clinics located in Erbil, where infertile women from varied socio-economic backgrounds and communities sought medical attention. In addition to collecting anthropometric measurements, a validated questionnaire was used to acquire data relevant to the factors that led to infertility, the length of time that a couple struggled to conceive, academic level, profession, and lifestyle choices. Clinical examinations have also been conducted on the sample that was provided. At the beginning of each interview with the subjects, both the aim of the research and its general outline were discussed. The participants' knowledge of the study's objectives and procedures was confirmed by the researchers. They were also informed that their involvement in the research was fully voluntary, their anonymity would be guaranteed, they may retire from the research at any moment, and the data they provided would be used only for the objective of the research. Additionally, they were informed that the analyst would be in charge of maintaining the security of the information and that they might ask for the removal of their information at any time. Women who were already afflicted with other serious illnesses, as well as those with a prior history of mental illness and cognitive impairments, were excluded from the study. The outcomes obtained in this manner have been evaluated carefully and reported.

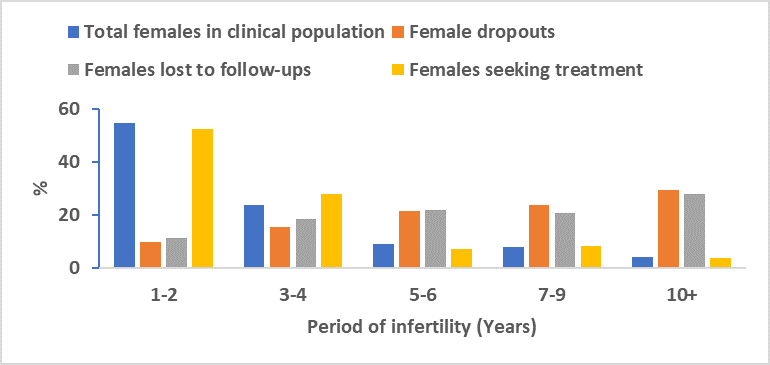

946 infertile females were included in the research, and the sample was organized based on the length of time they had been infertile. The ratio of participants who dropped out of the study, those who were lost to follow-up, and those who sought treatment for infertility are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. percentages of the clinical population's sample of female infertility

Only 595 out of 946 females are now seeking treatment for infertility, and 351 females have dropped out of the research due to the fact that their socio-economic conditions prevented them from participating or lost their follow-ups due to their male partners' resistance or unwillingness to cooperate. Figure 2 makes it abundantly clear that a greater proportion of infertile women sought treatment at specialized reproductive clinics within the first two years of their condition (55.32%). Contrarily, when the duration of infertility grows (10+ years), the percentage of infertile women who attended the clinics reduced (5.11%). The number of females seeking treatment, lost follow-ups, and dropouts all showed the same pattern. Table 1 displays the sample's distribution based on the types of disorders and infertility’s length.

Table 1. Sample distribution based on abnormalities and infertility duration

| Period of infertility (Years) | Abnormalities | |||

| Hormonal deficiency & others, % | Small size Uterus, % | Tubal Blocks, % | Ovulation Defect, % | |

| 1-2 | 49.92 | 36.20 | 61.79 | 56.12 |

| 3-4 | 10.00 | 43.44 | 25.12 | 29.72 |

| 5-6 | 10.00 | 10.86 | 8.03 | 6.27 |

| 7-9 | 25.00 | 9.65 | 7.53 | 8.25 |

| 10+ | 10.00 | 4.82 | 2.51 | 4.62 |

| Total (595) | 3.48 | 14.39 | 34.56 | 47.56 |

Ovulation defects (47.59%) predominate in a total of 595 infertile females, outnumbering conditions such as hormonal deficiencies (3.48%), a small uterus (14.39%), and tubal blocks (34.56%). In the early stages of infertility, the proportion of all abnormalities was higher. Weight, height, and body mass index (BMI) are shown in relation to infertile duration in Figure 3. It is clear from the data that as the duration of infertility lengthens, there is a corresponding increase in the mean weight, but there is a corresponding decrease in the mean height. When looking at Figure 3, it is easy to see that an increase in BMI is also associated with a longer duration of infertility.

Figure 3. The sample's distribution of infertile females by average weight, height, and BMI

In clinical population, the sample’s distribution is broken down into educational levels and periods of infertility, as shown in Figure 4. According to the results, levels of all educational status are shown to drop as the duration of infertility grows. The success of the investigation is better with higher education than with lower education. More participants were graduates (33.12%) in the early phases of infertility, which is defined as the first two years.

Figure 4. The clinical population's sample was distributed according to the length of infertility and educational achievement

Female infertility cases are distributed according to rating, with most instances being normal (58%) and only 32% requiring medical attention. The nature of the remaining 10% of instances can be described as refractory.

Hormonal imbalances, uterine issues, age-related variables, tubal blockages, ovulation issues, and decisions imposed by the modern lifestyle, such as an unfavorable legislative framework for assisted reproduction, anxiety, higher average age of people getting married, etc., could also contribute to infertility. In this study, we looked at the clinical population of infertile women. We found that the duration of infertility was correlated with lost follow-up patterns, dropout rates, and treatment-seeking. This makes it clear that as the female infertility period lengthens (10+ years), the percentages of women afflicted by infertility are trending downward (5.11%). The results from other regions may point to several etiological causes for the high dropout rate throughout infertility management (29,30). The effectiveness of treatment and the results of assisted reproductive technology have been proven to be impacted by excess weight. Being obese or having a high body fat percentage increases estrogen production, which the body perceives as birth control and lowers the likelihood of becoming pregnant (31,32). The current research results show a stronger relationship between infertility and body size, particularly throughout the infertile period. Female infertility is significantly influenced by age (31,33); the longer the infertile time, the higher the prevalence of obesity. 56.12% of ovulation problems and 61.79% of tubal block cases are more common in the first two years of infertility, according to the current study. Infertility can result from endometriosis, a non-cancerous disorder that can clog fallopian tubes and prevent the egg from entering the tube (34,35). Anovulation is frequently brought on by hormonal imbalance. Insufficient follicle production by women experiencing hormonal imbalance will prevent the ovule from developing (36). During the one-to-two-year period of infertility, we noticed 49.92% of cases of hormone deficit. In addition, our research found that a small size uterus was associated with 36.20% of cases of infertility in 3-4 years. According to the current study, the probability of an inspection being completed rises with education level, and as the duration of infertility lengthens, levels of all educational statuses decline.

Fertility issues can be avoided by leading a healthy lifestyle, visiting your physician frequently, and preserving a normal body weight. Prospects for conception are improved by recognizing and treating chronic conditions such as hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, and diabetes. Since infertility is a widespread and critical issue, health care programs should be implemented to address it. The need for healthcare should be related to the cultural circumstances of certain regions. Providing infertile women with the necessary socio-economic and medical support is essential for overcoming the issue. Medications, small surgical treatments, laparoscopic procedures, hormone therapy, and preconception failure prevention can all be used to treat female infertility.

None.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.